How Boston Children’s Hospital Stands Out in a Crowd of Standouts

// By Peter Hochstein //

Despite specializing in kids exclusively, Boston Children’s Hospital confronts a wall of competition that hospitals elsewhere might find daunting.

Despite specializing in kids exclusively, Boston Children’s Hospital confronts a wall of competition that hospitals elsewhere might find daunting.

Liz Vanzura, chief marketing officer for Boston Children’s advertising agency, MMB, can list 10 other local hospitals that treat children—among them such formidable names as Mass General, Tufts Medical Center, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Boston Children’s also competes with 10 big-name children’s specialty hospitals in cities around the nation and pulls in patients from around the world.

So 395-bed Boston Children’s has to fight hard to maintain its position. With a total of over 230 locations in eastern Massachusetts, ranging from a once-a-week clinic to five full-service campuses, and partnerships with community hospitals to operate pediatric emergency rooms and neonatal clinics, the hospital treats almost 600,000 patients a year. The loss of a small percentage of its traffic could cost it more patients than some small hospitals treat in a year.

Moreover, Boston Children’s once suffered from what Margaret Coughlin, senior vice president and chief marketing officer, calls “a false familiarity” with its brand.“The hospital was known,” she says, but people were fuzzy on why it had a strong reputation, a critical matter in a world where “patients today are actually shopping for their health care.”

“We wanted to position Boston Children’s as the very special and unique place that we are,” Coughlin says, so that “for any parent there is only one choice and that is, ‘I have to get my child to Boston Children’s.’”

There was also a secondary goal—building the hospital’s reputation among opinion leaders who ranged “from people who were doing ventures with us around [medical] discovery to doctors who might refer patients.” The hope was that “they, too, formed both a rational and an emotional bond with the brand and with the hospital,” Coughlin adds.

In a written response, Vanzura expands on those goals. Among them, she writes, is the goal of building “increased understanding that where a child gets treated really matters.”

The resulting advertising is an interesting combination of traditional and Internet media choices, and of emotional and rational messages, with traditional media doing much of the emotional heavy lifting and the Internet focusing more on some of the specifics.

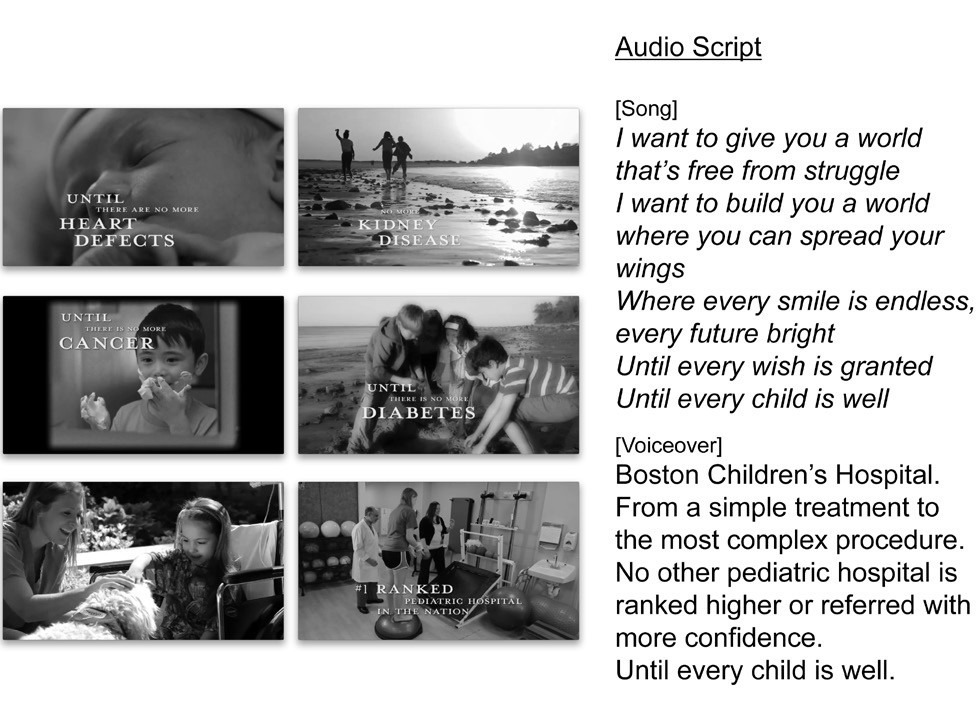

The television and radio advertising are built around a sentimental song, written for the campaign. It barely indicates it has anything to do with health care but sets a strong mood: “I want to give you a world that’s free from struggle/I want to build you a world where you can spread your wings/Where every smile is endless/ every future bright/ Until every wish is granted/ Until every child is well.”

The screen, meanwhile, is filled mostly with images of happy kids playing. Superimposed text (supers), nearly all beginning with the phrase “until there is no…,” lists serious conditions that kids have overcome, from heart ailments to kidney disease. There’s also a super indicating that Boston Children’s is the “#1 ranked pediatric hospital in the nation.” That ranking is reinforced by a “U.S. News Best Hospitals” seal.

The visual counterpoint of happy kids playing and the superimposed names of grave medical conditions, combined with a sentimental but positive song, help give these TV spots their impact. However, as the last frame shows, there’s always a rational claim to medical superiority, too. You can view the ad at http://tinyurl.com/q4s8yc3.

Images of sick kids were largely avoided, says Vanzura, because “we found that moms were tired of seeing that…. They wanted to see that you found a cure.” So the creative “focused on the ‘well’ side of the equation.”

The radio spots also employ the jingle, while in the early stages of print advertising one headline, “Until every child is well,” dominated. Meanwhile, the hospital established a strong presence in digital media, primarily on its own website and on Facebook, where Coughlin says many parents go to obtain and sometimes to share information.

One example of the content on the hospital’s Facebook page is a photo of a multivisceral transplant patient, looking happy and playful, celebrating his sixth transplant anniversary. He is bare-chested and wearing a cape. Deeper into the Facebook page, a parent of a different patient testifies about her daughter’s successful heart surgery.

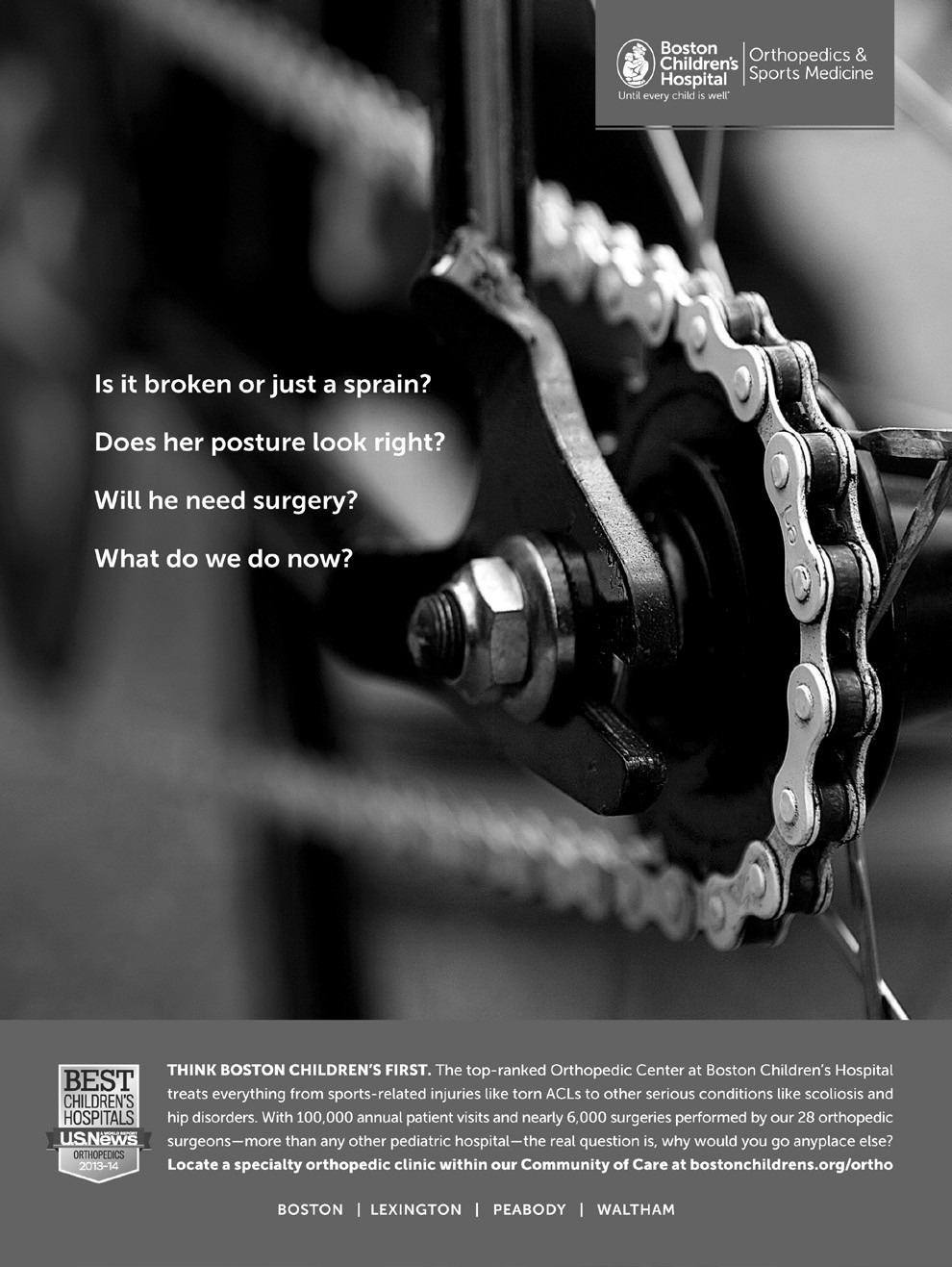

A “second stage” of print advertising reminded parents to use the hospital for less-than-life-threatening conditions, too. This ad refers to sports injuries, mentions the hospital’s “top-ranked Orthopedic Center,” and displays the “U.S. News Best Hospitals” seal.

Initially, “the campaign was looking to cast the widest net possible and used the widest range of media channels possible, which means more TV and radio” rather than “other targeted things,” Coughlin says. But the media mix has undergone regular modifications, based on research, to see “which channels were resonating most with consumers, which were generating the most action, and which channels were delivering the message.”

Some of the results of that monitoring may be surprisingly counterintuitive to many marketers. Print was the least effective medium, Coughlin reports. Digital advertising plus radio, not TV, “was the most powerful combination … that served the customers best and got them to get the information they wanted”

Note, however, that the TV spot appears both on Boston Children’s Web page and its Facebook page. So the TV effort may be contributing some horsepower to dig- ital. Moreover, says Coughlin, in the future, “we will be bringing back TV for a variety of marketing objectives.”

The varying media cocktail packs a potent punch. Extensive tracking research shows that although “intent to purchase” numbers were “somewhere in the 60 to mid-70 percent range before the campaign…for every single one of our product lines that I was measuring, we moved the intent to purchase by double digits,” Coughlin says. Between the first and second waves, she adds, “the minimum we moved was 11 percent, all the way up to 18 percent. Between the second and third waves we’re still seeing the numbers trend up.”

Hospital Marketing Tips Worth Saving

Margaret Coughlin says: “Listen, listen, listen to patients and prospective patients and then dig hard to understand how they make their buying decisions….What is the conversation between Mom and Dad when they’re trying to decide what to do for their child? Then figure out what really makes you different and unique [to them]. You’ve got something. You may not know what it is. It might [just] be something nobody else is claiming. So claim it.“Find that unassailable something that only you will be saying in the marketplace,” she adds. “Most hospital marketers stop before that last step, and therefore some huge percentage of hospital advertising in the marketplace makes them all look like one another.”Liz Vanzura adds: Keep track of what the end benefit really is. The hospital had a strong claim that it was No. 1 in its category in U.S. News & World Report, “but the goal was showing kids able to be kids again,” she says.

Peter Hochstein is a direct response advertising consultant, business journalist, and author. He can be reached through his website, http://peterhochstein.com.